This feature was inspired by the powerful reactions, debates, and reflections that followed my earlier Back in Time: Did You Know? posts. Your questions made one truth clear: we cannot fix what we refuse to understand. This work is offered in that spirit — not to condemn, but to clarify, so that healing becomes possible.

This feature was inspired by the powerful reactions, debates, and reflections that followed my earlier Back in Time: Did You Know? posts. Your questions made one truth clear: we cannot fix what we refuse to understand. This work is offered in that spirit — not to condemn, but to clarify, so that healing becomes possible.

A Painful Irony at the Birth of a Republic

Liberia became Africa’s first independent republic — a bold Black experiment in self-rule at a time when racism, slavery, and colonialism defined global power. Yet within this victory was a painful contradiction: the settlers who fled oppression in America began building a nation that placed them above the Indigenous majority they met on these shores. The oppressed did not become equal partners — they became the new ruling class.

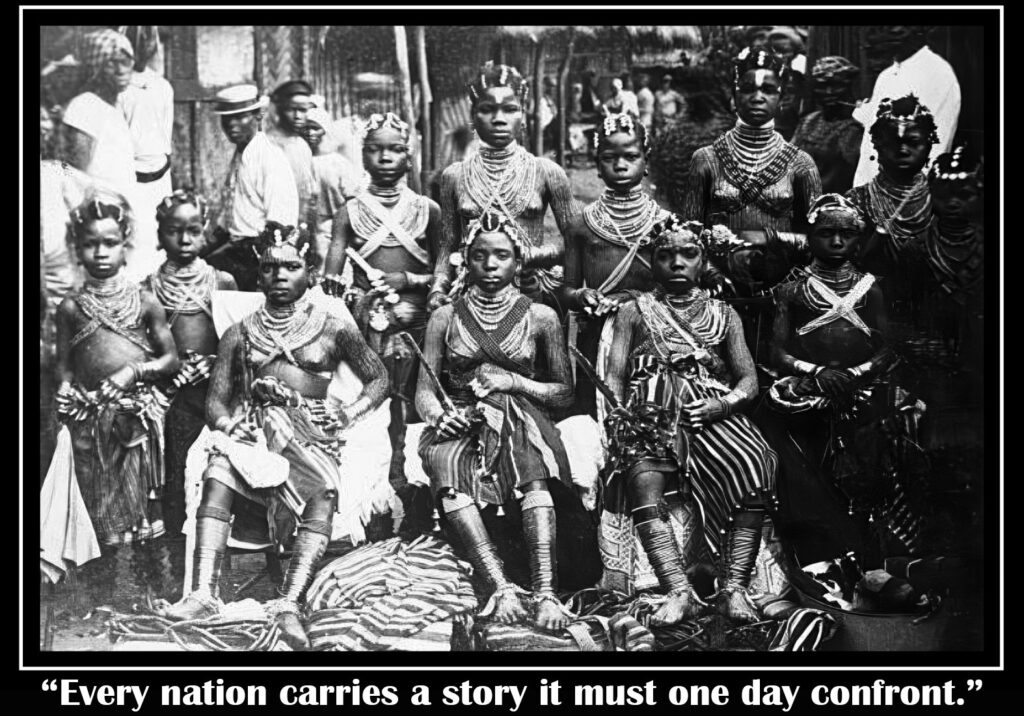

Two Worlds On One Soil

Indigenous communities lived through clan authority, ancestral lands, shared resources, and cultural continuity. The settlers carried Western legal systems, private property concepts, and a belief in “civilizing missions.” Instead of integration, the settlers built a government beside — and eventually above — local systems. This was the birth of two Liberias on one land.

How The System Took Root — Land, Law, And Leadership

Land became the foundation of power.

In 1857, the Legislature passed the Public Domain Law, declaring all non-deeded land as “public.” Communal land — the heart of Indigenous identity — was erased by pen, not consent.

Law became the instrument of division.

By 1904, a dual-legal system emerged: settlers under statutory law with full rights; Indigenous people under “customary” law with restricted rights. It meant two citizens under one flag — one protected by law, the other by tradition alone.

Leadership became the lever.

From the early 1900s through the Tubman era, only chiefs approved by Monrovia could lead. The strategy was simple: co-opt when useful; coerce when necessary — meaning, win local leaders through promises, titles, and recognition (co-optation), or force compliance when persuasion failed (coercion).

It is also important to remember that Indigenous communities were not monolithic — some chiefs resisted fiercely while others cooperated strategically, each trying to navigate survival in an unequal system.

Land — The Wound Beneath Our Feet

Land is emotional for every Liberian. For Indigenous communities, land is identity and ancestry. For settler families, land is legacy and proof of “civilization.” This is why land disputes today are not just legal — they are psychological inheritance.

In 1857, when all “unclaimed” land became state property, the foundation of exclusion was set. Those without a deed were branded tenants in their own homeland. For over a century, the “Mother Deed” — the first document proving title — became both symbol and safeguard for families. Generations guarded those papers as if they were sacred relics.

Did You Know?

A “Mother Deed” is the root document that proves original ownership of property. Without it, proving land rights can become nearly impossible — even if a family has lived on the same land for a hundred years.

The 2018 Land Rights Act, signed under President George M. Weah, marked a turning point. For the first time in our nation’s history, it recognized customary land ownership, including women’s rights to land. It was a landmark victory — the first true legal acknowledgment that Indigenous people owned their land long before Liberia became a state.

Yet the trauma remains. Some long-standing families now fear losing their generational property to new community claims, while rural communities struggle to document ancestral land before others do. It’s not just a legal issue — it damaged our sense of identity as a people.

But long before today’s land debates, these wounds were shaped by open resistance, shattered treaties, and military confrontations that defined the relationship between the state and its first peoples.

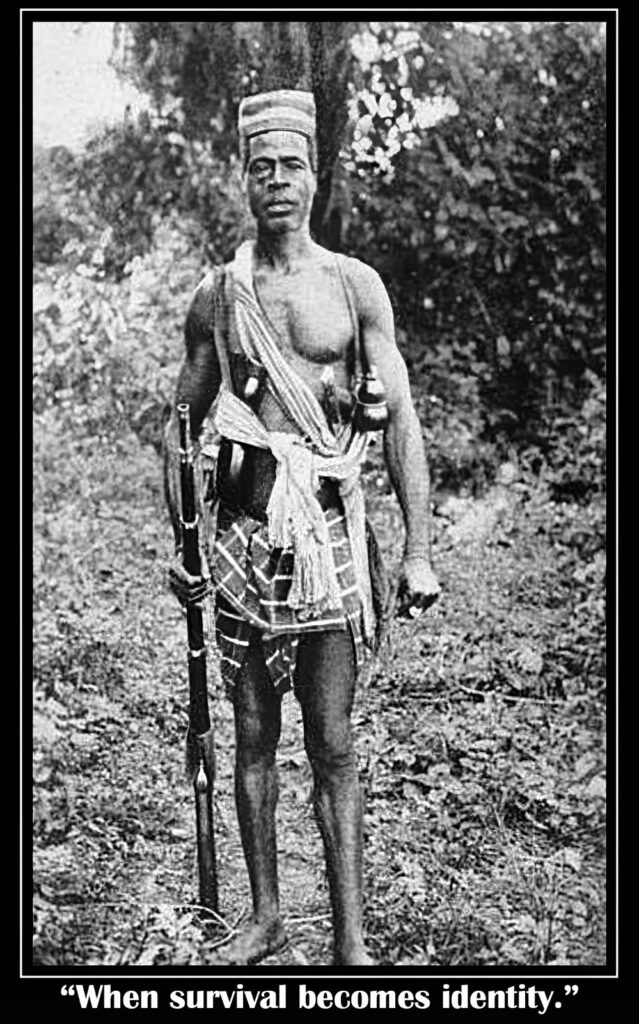

The Wars of Resistance — A People Who Refused to Disappear

Indigenous resistance was not passive — it was fierce, organized, and costly. The struggle was never about “refusing civilization,” as some falsely claim. It was about refusing erasure.

Did You Know?

The Republic of Maryland — also called Maryland in Liberia — was a short-lived independent Black republic on the West African coast, founded by freed African Americans from the U.S. state of Maryland. It declared independence in 1854 with its capital in Cape Palmas (Harper), but after conflict with the Grebo and Kru peoples and mounting economic pressure, it relinquished its sovereignty and joined Liberia in 1857, becoming today’s Maryland County.

Maryland–Grebo/Kru War (1856)

Grebo and Kru fighters resisted coastal domination and trade restrictions. The Republic of Maryland, unable to subdue them, called Liberia for military support. By 1857, after defeat,

Maryland was annexed — not by consent, but by force of reality.

Grebo War (1875–1876)

When Grebo communities again pushed back, the United States Navy intervened on behalf of the Liberian state through the USS Alaska. Diplomacy came with gunboats. Chiefs were pressured into surrender. The message was unmistakable: the state had foreign backing.

Kru Coast Rebellion (1915–1916)

Under President Daniel Edward Howard, the Kru again resisted state encroachment. The USS Chester arrived, anchoring the state’s position and breaking the uprising. Casualties were never fully recorded — Liberia counted its sovereignty, but not its Indigenous dead.

These conflicts reveal a truth we rarely confront: the Republic survived its early years not through national unity, but through military enforcement of a hierarchy.

Culture — The Long Road Back to Ourselves

While the physical battles raged, a cultural war quietly unfolded.

Western education, clothing, religion, speech, and taste became the currency of “civilized identity.” From coastal elite circles to schools and churches, a message spread: to be modern was to be Western.

I saw the legacy of that mindset with my own eyes. As a young DJ in the mid 1980s at Lipps Nightclub, I learned a simple truth:

If I wanted to close the party, all I had to do was play African music — people took it as their cue to leave. That was the mindset. Our own sound, our own rhythm, our own cultural heartbeat was considered “backward.”

Today, that same African music brings laughter, pride, and energy — especially in the diaspora. We dance to it all night. We wear African fabrics with joy. We reclaim our names, our drums, our languages, our beauty. The shame is fading — but the wound explains why it took so long to love ourselves.

African Proverb: “A man who does not know where the rain began to beat him cannot say where he dried his body.”

Our rain began with cultural shame. Our drying begins with cultural pride.

Poro & Sande Under Pressure — Then Co-Opted

Across the interior, the men’s Poro and women’s Sande societies were the core of local governance, initiation, identity, and justice. Their sacred groves, bush schools, and spiritual authority shaped leadership and social order.

But as the settler state claimed the interior and centralized authority, these societies faced a double assault:

State pressure — limiting their territory, regulating initiation, and undermining their authority

Missionary labeling — condemning sacred traditions as “pagan” or “uncivilized”

Eventually, politicians chose not to destroy Poro and Sande — but to co-opt them. Chiefs and Zoes aligned with state interests received recognition, salaries, and influence. Power shifted from the bush to the capital, and loyalty followed.

In many regions, no leader could rule without the blessing of Poro or Sande — until the state rewired the chain of authority.

Christianity and the “Civilizing Mission”

Christianity brought literacy, education, and faith — but it also became a tool of cultural control. Mission schools offered opportunity, yet often demanded the rejection of tradition as the price of entry. Churches helped frame Indigenous identity as inferior, which made the political hierarchy seem “moral.”

This is a part of our story we must face carefully and honestly: the cross and the court sometimes worked hand-in-hand.

The Long Fuse to 1980

By the 1970s, the fracture in Liberia had become a fault line. The divide was no longer just political — it was cultural, psychological, economic, and ancestral. Generations of Indigenous Liberians carried the memory of exclusion. Generations of settler-descendant families inherited a system they did not create, but benefited from.

Movements such as MOJA and the Progressive Alliance of Liberia (PAL) gave words to grievances that elders had carried quietly for decades. The youth, students, market women, and rural communities began demanding a Liberia that belonged to everyone, not some.

The Rice Riots of 1979, though triggered by economics, were fueled by history. When soldiers struck on April 12, 1980, they did not only overthrow a government — they punctured 133 years of unresolved tension. The First Republic did not collapse in a day. It cracked slowly from 1857 to 1980, until the weight of inequality brought it down.

Personalities — The Architects and the Resisters

Joseph Jenkins Roberts — symbol of the settler republic and the coastal founding vision.

Daniel Edward Howard — presided during the 1915–16 Kru uprising.

William V.S. Tubman — preached “Unification” yet strengthened centralized control.

William R. Tolbert Jr. — opened political space but inherited a system too wounded for quick healing.

On the other side of history stood Grebo, Kru, Gola, Bassa, Vai, Kpelle, Loma, Gio, and Mano elders and chiefs — from legendary Kpelle leader Suah Koko (c.1850–1934) and Nimba’s Chief Blahsue Vonleh (c.1880–1947) to Grebo leaders King Freeman and Weah Boleo (‘King Will’) — who resisted cultural erasure and defended ancestral lands. They were not ‘tribal obstacles’ — they were guardians of identity in a struggle that predated the Republic.

Did You Know?

During the Grebo resistance of the 19th century, leaders such as King Freeman and Weah Boleo (“King Will”) emerged as central figures in defending coastal territory against both the Republic of Maryland and later the Liberian state. Their resistance helped define the Grebo reputation as one of the most formidable Indigenous forces in early Liberian history.

I know some will ask why I, as an Americo-Liberian, would “go there” instead of protecting my side of the story. I expect the inbox messages and the quiet grumblings. But this is exactly our national problem: we avoid truth in the name of peace, and in doing so, we protect wounds instead of healing them. Silence has handcuffed us. Avoidance has paralyzed us. A nation cannot mature if its history is edited to spare egos. I do not write to shame my heritage or erase its contributions, but to confront its failures with honesty — because love of country means loving the truth about it. Only then can we fix what we broke, together, and finally move forward as one people. And if we do so with courage, this approach will lead to a lasting solution that creates a pathway to a brighter future for the generations that will follow.

These legal shadows did not disappear with time — they followed the Republic for generations.

Did You Know?

The Public Domain Law of 1857 and the 1904 dual-legal system remained pillars of inequality for over a century, shaping land ownership, citizenship, and political power into the late 20th century.

A Path Forward — If We Are Willing to Mature as a Nation

Liberia can learn from its past instead of reliving it. But healing requires honesty, not hostility.

Harmonize Land Ownership

Protect both deeded families and customary communities through a single transparent national land registry. Customary land rights and deed rights can coexist — but under clarity, not chaos.

Dialogue, Not Default to Court

Land is emotional inheritance. Mediation must come before litigation. Too many cases today are personal wounds disguised as legal disputes.

Cultural Confidence

Teach our dialects. Wear our clothes. Celebrate our music. A people ashamed of themselves can never build a confident nation.

Teach the Whole History

Schools must teach both Liberias, not one side. Unity begins with truth.

As our elders say, “One hand can’t tie bundle” — a nation cannot hold together when only a few control the rope and the rest are left watching.

From an Americo-Liberian Voice

I do not write this to blame my ancestors or silence the pain of Indigenous Liberians. I write because truth is not betrayal. Truth is nation-building. Our forefathers built a republic, but not a nation. It falls to us to finish the work — differently, and better.

A Hopeful Close — The Future Is Bigger Than the Past

Liberia’s story is painful, but it is not hopeless. We can choose unity over pride, fairness over fear, and memory over myth. A nation once divided can be made whole — if we are willing to face our past without rage, and our future without fear.

A Shared Educational Journey

This work is part of a shared historical journey. If you have verifiable records, documents, or firsthand accounts that can expand, clarify, or correct any portion of this narrative, I welcome them. Our goal is not to argue, but to understand — together — the story of who we were and what it continues to teach us today.

Researched and written by Derek M. Moore

#BackInTime #DidYouKnow #KnowYourHistory